#Trendlecciones

Búsquedas electorales en México 2018

Búsquedas electorales en México 2018

Probably one of the most complex issues during the electoral season is trying to understand what is going on. We often see politicians trying to sell themselves and alliances/breakups between parties; we see debates, we hear radio spots and we read polls, studies and op-eds that try to decode these complicated movements. We face a huge information saturation that is oftentimes biased, and sometimes contradictory or even incomplete.

To get a glimpse of the electoral outlook, one of the most used tools are public opinion analyses. These try not only to reflect electoral preferences, but explore how does the general opinion change through time and other factors such as age of the electorate, scholar levels, geographic regions, genders, etc. However, after reading these we are often left with more questions than answers: Why is a certain candidate so popular? What is the importance of debates and proposals? How would an specific event affect the general opinion? We can approach these questions from an individual perspective by thinking, for example, that some voters prefer specific proposals thanks to their personalities. Or infer that an specific event should change preferences in some ways. However, in many cases, these predictions and deductions may be wrong. General opinion is unpredictable: it can change rapidly or remain static after we thought an event could transform it.

Perhaps, considering that voting is an action that goes beyond an individual choice and transcends the moment in which we cast out vote can help us comprehend the electoral process in a different way. As Popkin states (1991):

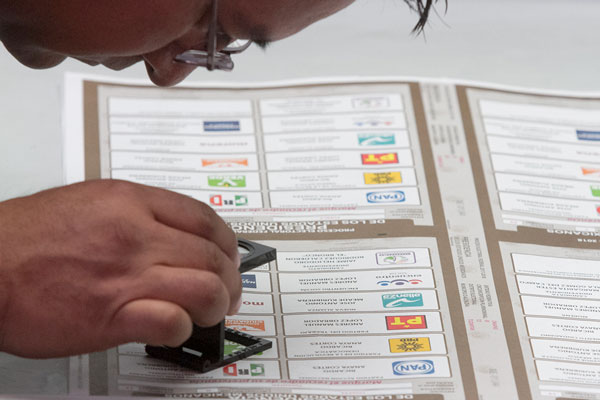

Voting is a social act, a collective action not only in its consequences but in the ways that both the choice and the action of voting is configured.This is more evident on the election day. As we arrive to the polling booths we encounter the result of a highly complex electoral system, which takes months, and even years, to organize. This system operates electoral campaigns, trains citizens to take care of the booths, distributes voting papers and counts votes so it can deliver results just a few hours away after we show up and cast our votes.

Voting is a social action because it involves a complex series of interactions (we are sometimes invisible or unconscious). These interactions are essential to understand the way in which we make our decisions of who are we going to vote for, or why we are not voting for someone. The election day is not a one day process but a very complex system that takes months, even years. Millions of people are involved in it. To take this interactions into account by analyzing them allows us to reflect on the complexity of the electoral process. We can track patterns, connections, and some not-so-obvious things that are fundamentally indispensable in the process.

Voting is a public and private choice at the same time. It is private because it involves individual thought processes in which we reflect about the candidates: we imagine possible scenarios and we pounder between the consequences (good or bad) that this decision can have in our lives. We analize proposals and we react to the candidates, their personalities, their social context, their experience, how do they talk, and the people that surround them.

Besides from the rational side, voting is also about feelings. Most of the time we make emotive decisions that can be acknowledged on discussions, debates and even opinion analysis. Often, this emotive side finds more presence on our individual spaces, on our intimacy, and it can be better reflected on trends analysis rather than polls, for example. In private we face our fears to long-term goals and immediate expectations. We identify our fears and illusions, and what we expect from our future and our present. And, most importantly, we assume that we think about ourselves and the world from a certain perspective: from this position we make choices.

Voting is public too because we do not decide in isolation. We interact in an specific ambient by talking with others, hearing about others, reading the media; we are interested in what our friends think… and also in what our enemies believe

People express opinions that would not be public if it were not because of the election days. Things get heated.Irrelevant things can acquire relevance. For a lot of people, the election process is a time of discussions with close friends and family. Sometimes, these conversations tighten relationships; in other cases, conflict arises and separations may happen.

To think about the action of voting as a social thing can help us comprehend it in different ways. It can make us realize that the election results are just a small piece of what voting means. It implies that we acknowledge the vote is an action in which egoism and collective thinking are in constant tension, where quotes like “this is the best for me and my family”, “this is a project I relate to”, and “This candidate is the best option for our country” are in a constant and tense dialogue. In other words: we are part of something bigger than us.

Popkin, Samuel L. 1991. The Reasoning Voter. Communication and Persuasion in Presidential Campaigns. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago, IL. http://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/R/bo3636475.html.